Some thoughts on the short fiction of Frank O’Connor

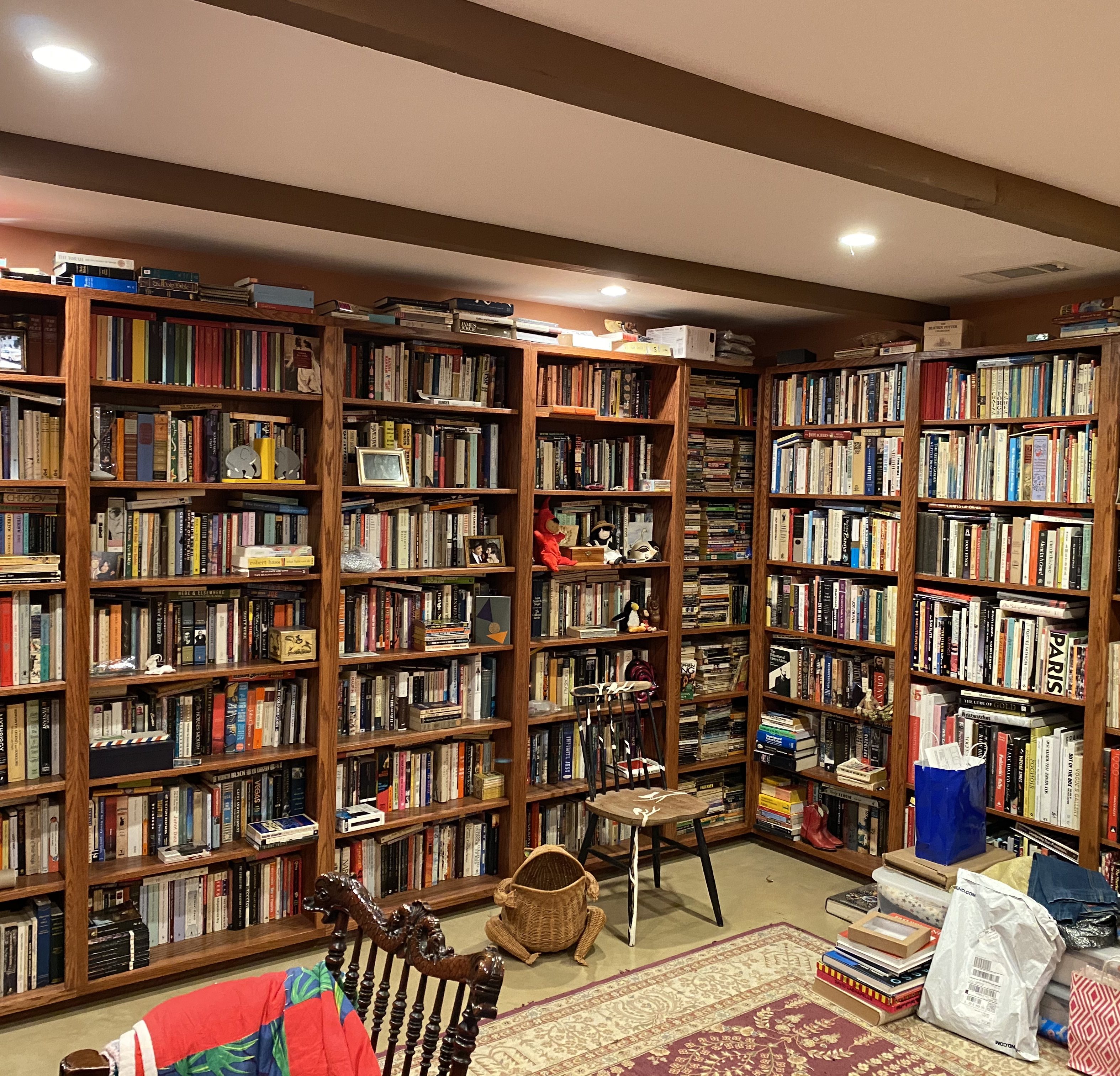

How has your quarantine reading been going? Are you tackling those big doorstops that you’ve always meant to get to or is your attention span only focused enough for micro short fiction? Have you preferred to lose yourself in escapist fiction, bend your mind with the experimental stuff or face up to facts with realism?

Of course, there are no right answers here, and in my case, I will most likely find myself touching several of those bases. To begin with, I spent the first month of quarantine reading Frank O’Connor’s Collected Stories. As much as I could focus and immerse myself in the world of his short fiction, I immensely enjoyed this experience.

The Collected Stories opens with arguably his most famous story, “Guests of the Nation.” It’s a stunner. A group of Irish Republican soldiers are guarding a couple of captured British soldiers. The banter between the two groups is easy going. The narrator of the story enjoys the Brits’ easy going humor and their political debates—one of them is a socialist who sees the strife in Ireland through a class conflict lens. It is assumed by all that the soldiers are being held for a prisoner exchange. The story turns when the order comes down to execute the Brits in retaliation for the killing of Irish soldiers.

The narrator and his colleagues are stunned by the order though they reluctantly carry it out. The unfolding horror of the execution is portrayed in an understated, matter of fact manner. It is a masterful story that will remind Isaac Babel readers of his Red Army stories. As it so happens, Babel was a stated influence on O’Connor’s writing. While there are a few other Republican Army stories in this collection, the bulk of them are more domestic tales based in the either in the city of Cork or in the countryside. Among my favorites are the ones based on his childhood. The most famous of these is “My Oedipus Complex,” a wry tale of the battles that a mother-attached boy wages with his just returned from the war father. A twist at the end of the story makes for high ironic comedy.

O’Connor is especially strong at capturing the viewpoints of children—their selfishness and anxieties. The boys are often closer to the mothers though yearning for attention from their often alcoholic fathers (a persistent theme in O’Connor’s fiction). His depiction of girls and women in general is quite fascinating. On one level they appear to be mean, bitchy, and closed off, intimidating, if not terrifying the boys and men who encounter them. The usually male narrators frequently make wry comments about the difficulty of women’s attitudes and behavior, which certainly should be interpreted as misogynistic, but not necessarily reflective of the author’s beliefs.

In fact, a sustained reading of O’Connor’s work has led me to believe that his female characters are presented with deep sensitivity, and that the sometimes boorish attitudes of his narrators are meant to be taken with a good dose of irony.

The position of women in O’Connor’s stories is difficult. They are constrained by the church and its draconian attitudes, as well as often self-absorbed, bitter, unreliable, and the aforementioned frequently alcoholic men. In various instances they use their intelligence or patience or faith to endure their difficult circumstances. In the course of these stories, which are arranged chronologically in order of publication, O’Connor’s skill in portraying women deepens in subtlety and psychological richness grows—so it seems to me anyway.

One of the most fascinating of his “relationship” stories is “There Is a Lone House,” in which an unnamed woman with a family secret who lives alone takes in an unnamed younger man who is a wandering laborer. The man does work for the woman in exchange for shelter. In time they become lovers. Eventually the man grows restless, but he eventually returns. Their relationship is passionate and contentious. It changes both of them but it’s complicated, as defined in this passage.

“It seemed a physical rather than a spiritual change. Line by line her features divested themselves of strain, and her body seemed to fall into easier, more graceful curves. It would not be untrue to say she scarcely thought of the man, unless it was with some slight relief to find herself alone again. Her thoughts were all contracted within herself.”

On one level, this is the woman’s sexual reawakening, triggered perhaps by her unnamed lover’s virility, but it is sustained and deepened by her own reserves and emotional intelligence, as the man discovers time and again: “He had felt in him this new, lusty manhood, and returned with the intention of dominating her, only to find she too had grown, and still outstripped him.” The pair’s path to mutual respect and accommodation is hard won and solid in spite of the revelation of the woman’s secret (I won’t give it away). Dignity, self and mutual respect, are achieved in this impressive story of the growth of a mature relationship.

O’Connor’s later stories (this collection presents them in chronological order of publication) are largely focused on death. My favorite of these tales is “The Story Teller,” in which a young girl’s beloved, tale spinning, seemingly pagan grandfather is dying. He has scandalized his more religious children with his scorning of the church and his embrace of Irish folklore and stories. Afric, the little girl, fully expects her grandfather to be borne away from life by the mysterious figures in the tales that he has enchanted her with. She ignores the judgmental comments of her family members as they speak of their patriarch’s lifelong blasphemy as she keeps the faith in her grandfather’s stories. However, no magical moments happen as her grandfather quietly slips away.

“There was no farewell, no clatter of silver oars or rowlocks as magic took her childhood away. Nothing, nothing at all. With a strange choking in her throat she went slowly back to the house. She thought that maybe she knew now why her grandfather had been so sad.”

It is a bittersweet, if not crushing moment in a little girl’s life, but perhaps also a statement of purpose of the writer’s life: forging ahead with the work of storytelling in the face of inevitable disappointment and decline. Good practices to consider in the midst of a grim pandemic. And what a pleasure and comfort to muse on these notions while reading these wonderful stories.